With Coral Reefs in Hot Water, Bermuda Could be a Safe Haven

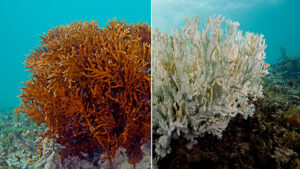

A fire coral before and after bleaching. The one on the left is a healthy fire coral, while the one on the right is completely bleached. Photo by XL Catlin Seaview Survey.

Elevated ocean temperatures have threatened coral reefs around the world for over a year, but this October marked a tipping point. NOAA scientists declared the onset of a global coral reef bleaching event impacting coral reefs in every ocean basin, and projected the bleaching will only intensify in 2016. This is the third such global bleaching event in history.

Many forces are at play in the global bleaching event. El Niño has brought warm, tropical waters to places in the Pacific that are ordinarily cool, and a stagnant warm-water formation known as “the blob” in the northeastern Pacific is producing the worst bleaching event ever seen in the Hawaiian Islands. With 2015 on track to be the hottest year on record, coral reefs in the Caribbean have been exposed to sustained temperatures outside their comfort zone, and widespread bleaching hit Florida’s reefs in August.

But with the exception of some fire coral that bleached at the end of the summer, Bermuda’s coral reefs have not been hurt by the current global bleaching event.

Bleaching occurs when high temperatures, or other stressful conditions, cause corals to expel the symbiotic algae that live within their tissues. The algae ordinarily provide food for the coral, as well as the distinctive colors of coral reefs. When the symbiotic algae are lost, the corals turn ghostly white in what is known as a bleaching event.

While bleaching isn’t a death sentence – corals can recruit new symbiotic algae from the water and return to health – the longer the stressful conditions persist, the lower the chance of recovery. The first global coral bleaching event came in 1998 on the heels of a strong El Niño, and killed up to 70 percent of corals at some sites in the Indian Ocean.

Summer heat rarely has the chance to cause lasting bleaching damage in Bermuda. Compared to the Caribbean, Bermuda’s more temperate climate limits the window in which water temperatures can exceed the average annual high to induce bleaching. Reduced bleaching events are “one of the joys of being a high latitude reef,” said BIOS coral reef scientist Dr. Samantha de Putron. But living on the edge of a tropical range comes with another unique set of challenges.

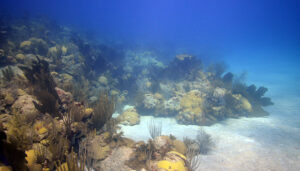

A healthy reef in Bermuda. Photo by Eric Hochberg.

Coral reefs “prefer” water in the range of 75-82F, with a lower temperature limit of 64F – which is the average winter water temperature in Bermuda. That means in the winter, Bermuda’s reefs experience occasional dips down to 60F water temperature. Understanding the biology behind coral resilience at both high and low temperature extremes is essential for understanding how corals might survive future climate change scenarios. Using experiments in the lab and field, de Putron and visiting Brazilian graduate student Lais Lima are studying how the hardy lesser starlet corals (Siderastrea species) respond to cold stress. They plan to replicate their Bermuda experiments in Brazil to compare corals at both ends of the geographic range.

If corals in the Caribbean fail to recover from future bleaching events, Bermuda’s reefs may provide a safe haven for many coral species. BIOS coral reef scientist Dr. Gretchen Goodbody-Gringley has used genetic techniques to study whether coral populations from Bermuda and other sites around the Caribbean are isolated from each other or interbreeding. She found evidence that some populations can interbreed and exchange offspring, and that currents carrying coral larvae can connect reefs across the region.

Thus, healthy reefs in Bermuda could help maintain coral diversity in the Atlantic, which is yet another reason to take good care of our reefs.

Bermudians have already made great strides caring for corals. A major international study analyzing how Caribbean reefs have changed over the past 40 years highlights Bermuda’s ban of fish pots, as well as the protection of parrotfish, as key mechanisms safeguarding reef health. Parrotfish grazing on the reef defend corals from seaweed that could otherwise smother corals in distress. As these fish have been removed from much of the Caribbean, algae tends to take over bleached coral and once thriving reefs are reduced to rubble and seaweed.

Furthermore, the ability of corals to recover from any single bleaching events depends on their overall stress level. Limiting local pollution and maintaining a balanced ecosystem helps corals survive stress from climactic events.

“When we minimize local stressors,” Goodbody-Gringley said, “corals facing bleaching have a stronger leg to stand on.”